I’m going to go a bit ‘off-topic’ from my typical Agile, Leadership, Lean, Software, etc. topics and try and provide some information that may help people in these communities. With so many states starting to open up businesses and such, you may be wondering how you can decide when you can plan your conference or meet-up to start meeting in-person again.

So we’re going to focus on a formula that George Mason economics professor Alex Tabarrok wrote. You can find the details behind this at his post COVID-19 Event Risk Assessment Planner. This assessment planner focuses on the US population in its risk assessment. One of my primary concerns is to help people that plan regional events and meet-ups.

Stand by, we’re going to be doing some math….

In that article, there is a formula:

1-1(1 – c/p)^g

from COVID-19 Event Risk Planner by Professor Alex Tabarrok

Where c = the number of people carrying the disease, p = the population, and g = the group size planned for the event.

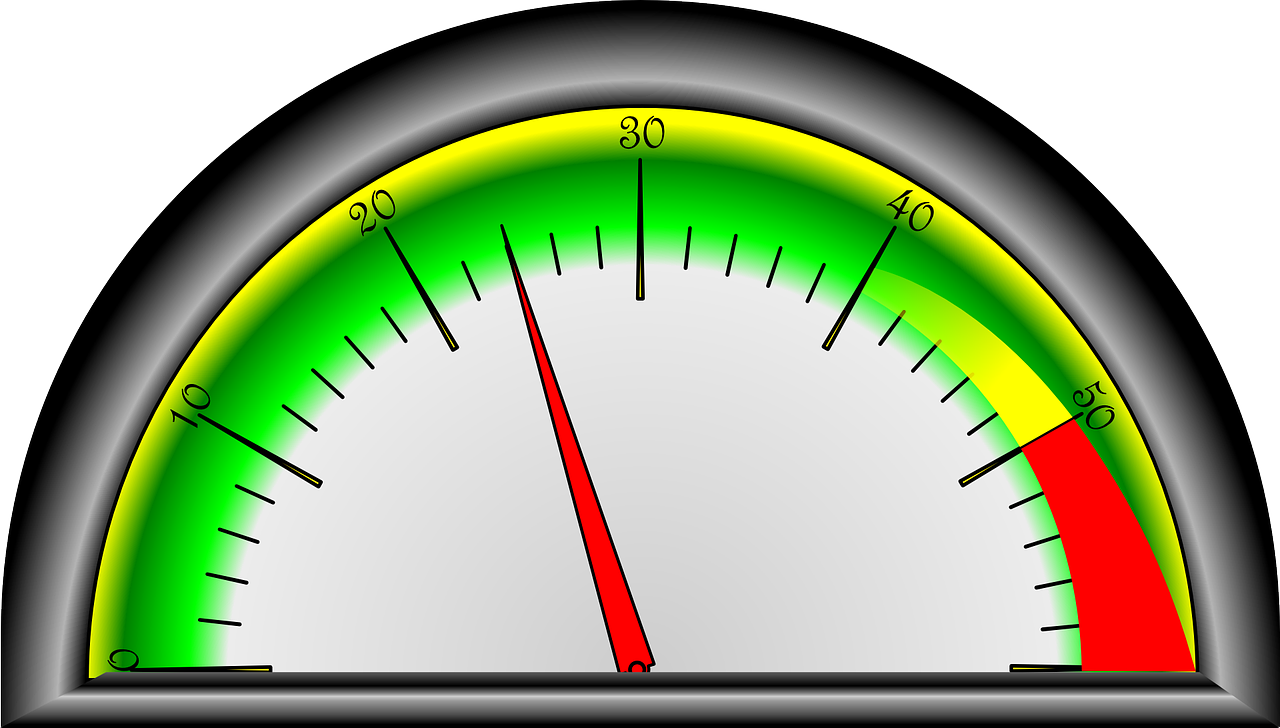

He has a nifty graph also that shows this for the US. (Though we now have gone off the scale on the left hand side, so it would be worth extending it.) Note that this is a logarithmic graph, so I’d recommend recreating it on logarithmic graph paper.

When planning a regional event like a meet-up though a calculation at the US level (or any other country) is probably inappropriate. Here is how you can extend that to a regional view…

I am going to do some calculations based on two meet-up groups here in Virginia as a start. First is the Games for Agility, Learning, and Engagement (GALE) meet-up we hold at Excella. It is based in Arlington, VA and draws people from a few surrounding counties and cities (DC, Alexandria, and Fairfax County mostly). [Note: I’ll show what happens if I add in Montgomery County in a moment.]

So first I need to know the populations. Some googling gives me the following:

| City or County | Population |

|---|---|

| Arlington | 237,000 |

| Alexandria | 144,000 |

| DC | 702,000 |

| Fairfax | 1,010,000 |

These numbers were from 2019 projections taken through google search results and rounded up to the nearest 1000. These should be good enough… So the total population about is 2.093 million. We’ll set that aside for now…

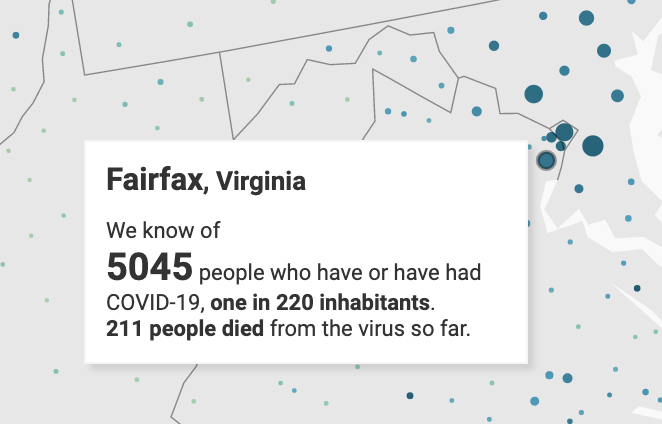

Next we need to figure out the number of carriers. For this I am going to turn to the wonderful graphics from the Data Wrapper page on 17 (or so) responsible live visualizations about the coronavirus, for you to use and in particular the map portrayal titled: Number of confirmed COVID–19 cases in US counties. (You will need to scroll down about 2/3 the page – the page has lots of graphics on it, so expect it to load a little slow.) I’ll zoom in a bit and scroll over to Virginia.) This data gets pulled daily from a set of data at Johns Hopkins University.

We’ll pull the ratio that reflects the ratio of the population that is infected. I could pull just the number known I suppose, but it states that number has or had, which means it includes deaths (people no longer around) and recovered (people who no longer have the disease). I get this by hovering over the appropriate dot. So here is an example:

Let’s add this information to our table:

| County | Population | Ratio | Calculated Carriers |

|---|---|---|---|

| Arlington | 237,000 | 1:180 | 1317 |

| Alexandria | 144,000 | 1:150 | 960 |

| DC | 702,000 | 1:120 | 5850 |

| Fairfax | 1,010,000 | 1:220 | 4591 |

This makes the total number of carriers we’ll use as 12,718.

We need one more number before we can run the numbers through the formula. The size of the group. So using GALE first as our example. Our largest in-person meet-up size was 16 (we’re a small niche interest….). This goes in for the g in the formula, which you will observe is a factorial. As Alex writes in his Risk Assessment Planning post, this is the biggest factor in determining risk as it is bringing people from the population that has been exposed together.

Running the numbers…

1-1(1-12718/2093000)^16=.092… or about 9%

So if I ran GALE today, there is an almost 1 in 10 chance someone in the crowd would be bringing the disease (unknowingly) into the meet-up group. Personally, I’d want this to be below 1 in 500 (0.2%) before I’d feel comfortable (that’s a meet-up group of 3 in case you are wondering).

Let’s now look at how the DC-Scrum User’s Group would look. They regularly have 50 people showing…

1-1(1-12718/2093000)^50=.262… or about 26%

This means they have better than a 1 in 4 chance. Yikes! But wait, they regularly pull people in from Montgomery county, MD also. Mongomery county’s population is 1,051,000 with an infection rate currently of 1:170. This yields an additional 6182 carriers. So for the same size group the formula looks like…

1-1(1-18900/3144000)^50=.260… or still about 26%

Not much change. But if 60 people decided to come I’m now at about 30% chance of someone being a carrier.

If you are deciding to restart your in-person meet-up, the guidance I would advise on this is to cap the maximum number of attendees AND be transparent on the percent chance someone would be a carrier. (If you could set-up the meet-up such that it had social distance as a part of it and perhaps specified masks you might be able to allow a slightly higher risk than what the numbers may indicate as the formula isn’t factoring those things in.

If I were planning a multi-state regional event, I would use the population and ratios of the states attendees would be coming from… plus the ratios of the counties or cities of where speakers were coming from… if different from the attendees. So for example, Agile & Beyond frequently gets attendees from not only Michigan, but also Ohio, Pennsylvania, Ontario, Indiana, and Illinois. I’ve spoken at Agile & Beyond (so factor in Fairfax County, VA if I am selected); so has George Dinwiddie, so factor in his county as well.

I’d consider at this point calculating a straight average of the infection ratio and throw out any that were outside a significant factor different. Example, all my ratios are between 1/120 and 1/330, but two speakers come from places where ratios are 1/2730 and 1/1850; I would throw these low ratios out. I would not throw out an outlier at a higher ratio. This averaging with throwing these out would actually bias it to be conservative and thus safer for everyone.

For international events, you can use the countries from where people are attending.

How can we project when we can return to in-person events? The COVID-19 tracker at Virginia Department of Health provides a hint. If you look at the Number of cases by event date graph it is showing a downward trend, but we need this graph with the total number of infections in the population, not by event (which is a daily number). Then one can use the rolling average on the rate of change over say 3-7 days to project how the # of carriers will change. Perhaps you could do this with the number of daily events; I just don’t feel comfortable with that projection as the disease persists and daily events are more sensitive to social distancing, business closures, and other lockdown policies.

Another place to keep your eyes on is the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (IHME.org), they are the organization producing the models that forecast deaths, hospital usage, etc. and these take into account changes in patterns of mobility and social distancing. Hopefully we’ll start seeing some additional projections of rates of changes in infection rates actually being produced.

I hope this is helpful for people that are trying to figure out when and how to plan in-person events again.